Reaping: How ripe wheat used to be cut and dried at harvest time

Reaping is the process of cutting and drying a field of cereal, any cereal, a crucial part of bringing in the harvest. This page describes the process of reaping in fields of wheat in early 20th Century Britain, as remembered from personal experience.

____

By the Neil Cryer who watched reaping as a child

Important note: Before WW2, 'corn' in the UK meant wheat, whereas in America it meant maize, a little-grown crop in Britain at the time. A cornfield was a field of wheat.

Meaning of 'reaping'

Today, reaping is generally thought of as obtaining something good as a direct result of various actions - but it owes its origins to bringing in the harvest. A good harvest was essential if people were to eat in the following year, and it was the result of the hard work of ploughing and sowing months before.

Once a cornfield was considered ripe and the weather was dry, it had to be cut. This process was known as 'reaping'. I saw a lot of it in my childhood in the early 1940s. By then there were reaping machines, but for the odd-shaped corner, men used scythes to cut by hand.

Scythes: difference between scythes and sickles

In awkward areas of a field, men had to cut by hand using a long, curved blade known as a scythe. This was very effective, but was a knack that few of the younger men bothered to learn.

Sickles are smaller than scythes. What distinguished the scythes from large sickles was that the scythes had two grips, slightly offset from one another. Scything was a two-handed job. Sickles being much smaller, were designed for one-handed use.

Above: Sickle, designed for light work using just one hand.

Left: Old English scythe. Note the two offset wooden grips in the wooden handle and the relatively small angle between the blade and the handle.

My father had a scythe and I tried to use it once with no success at all, although I was given to understand that it was very efficient in experienced hands. Apparently there was a rhythm to using it and one's back had to be kept upright, with a side-to-side rotation of the torso making the cutting action - not the shoulders.

Scythe blades had to be sharpened frequently; a blunt blade led to inefficient cutting with the user grunting and flailing around.

The reaper or reaper-binder machine

In the 1940s, the combine harvester was still years away in the UK, although we heard that it existed in America. Our machine was called a reaper or reaper-binder.

Sheaves

The reaper-binder merely cut the corn and bound it with wire into loose bundles called sheaves. It was developed in late Victorian times and was pulled along by one or more farm horses or a tractor. There were various versions which are outside the scope of this website.

The reaper machine started round the edge of the field and circled round into the centre, producing an ever-decreasing 'island' of corn and leaving the bunches of cut corn lying on the short, harsh and prickly stubble.

The ever-decreasing 'island' of corn in the centre of a field while the corn is being cut.

The rabbits emerge

As the 'island' got smaller, the local wildlife ran out to escape, as described on the shooting parties page.

This is the point where children were needed, and why I was present at so much reaping. My friends and I had to watch out for the rabbits which would run out from the remaining crop. These rabbits were in dire trouble once they had broken cover and started for the safety of the hedges round the field. They couldn't run fast because of the sharp stubble, so they were easy to chase. Our task was to reach them and hit them over the head with a heavy stick to kill them.

At the end of the day, it was common practice for the farmer to go round on his tractor to collect all the dead rabbits. Then he would share them out amongst the helpers. I would regularly come home with a couple of rabbits for my mother to cook. Their preparation was messy and time-consuming, but this was a period of severe rationing. So the rabbit meat was very welcome.

From sheaves to stooks

If the sheaves had been left lying flat on the ground, they would never dry well enough for the grain to be separated out. So they were manhandled into what were known as stooks to dry in the sun. A stook was a group of sheaves which were stood up against each other, the ears of grain uppermost.

Good weather was crucial for complete drying. A little rain didn't matter at this stage, though, as long as there was enough sunshine to dry the stooks afterwards.

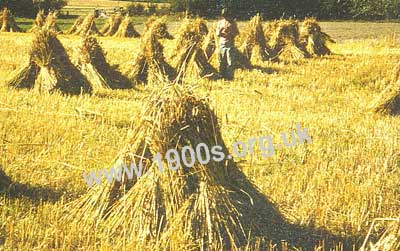

A field of stooks. The front one clearly shows that it is made up of loosely bound bunches of sheaves propping each other up, ears uppermost. The harsh stubble around each stook is clearly visible.

My friends and I were often involved in going round and standing the sheaves up into stooks to keep the grain as dry as possible. It was easy. We only had to pick up a sheaf in each hand and lean the two together to get them to stand up. Four or five such pairs of sheaves made a stable stook.

Tractor pulling rotating cutters to cut the corn, with workers in the background making stooks from sheaves - drawing from an old children's book.

Food and refreshments for the workers

Bringing in the harvest was hard work which lasted from dawn to dusk because good weather had to be used while it lasted. (These harvests were later in the season than today's, as explained on the bygone harvests page.)

contributed by V. John Batten

For their refreshment, the workers that I knew brought along a bottle of cold tea without milk or sugar and a couple of fat bacon or cheese sandwiches. There was also a nosebag for the horses. At the end of the day, an empty nosebag served as a handy place to carry home a rabbit for the pot provided that a fox or badger hadn't got in first.

contributed by Pamela Southin

My aunt used to prepare a picnic tea for the men who were harvesting. We took a large basket out to where they were working and set down a check tablecloth on some stubble in a corner of the field.

| sources | webmaster | contact |

Text and images are copyright

If you can add anything to this page or provide a photo, please contact me.