From clay in the ground to finished plant pots

Using the Cole Pottery in Tottenham as an example, this page explores the old working practices which brought clay from the ground to fully functioning plant pots. It brings the process to life through the contributions from the people involved; told by a descendant of the Cole family.

____

by the webmaster: family recollections and research

Extracting the clay from the ground

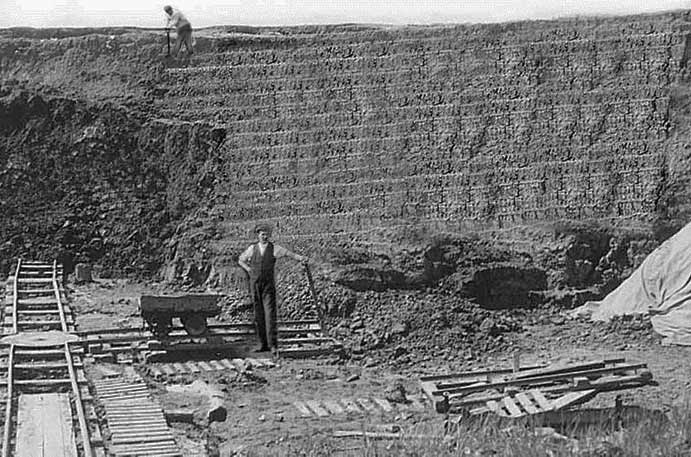

The clay for the pots was dug out from the ground by hand by the pottery workers. The digging caused a pit, known as a clay pit. The deeper it was dug, the deeper became the undug clay at the side, which was known as a clay mountain.

contributed David Marden, a child living at the pottery in the 1950s

The clay was hand dug with flat bladed spades which were lubricated with water to prevent clinging. The digging formed lateral steps that rose upwards to form a steep face at the working end of the clay pit, up to as much as the height of a house.

My reconstruction from memory. The clay pit showing the steps as the clay was dug out. The man at the top left is in the process of digging.

Once dug out, the clay was thrown down to ground level where it was moistened with water and covered with tarpaulins, as shown on the right to keep it wet.

Then it was loaded into small rail wagons on a single-track railway, as shown, which could be moved around as required.

The left-hand side of the image shows the unworked clay deposits waiting to be dug.

Subsequent digging created a new set of steps as work advanced into the face of the pit shown on the left,

In quiet times, when the pottery was not working, adventurous local children would climb the steps which felt like quite an achievement. The most freshly dug steps were the best to climb in spite of being rather slippery, as the older, drier ones crumbled underfoot.

Refining the clay: the mill and mincer

contributed Frank Marden, pottery worker in the 1950s

The stones and other impurities in the dug clay were removed in the pottery mill, also known as the pugmill.

A winch hauled the wagons up to the top of mill. A gantry over the works entrance led to the top of the mill where the wagons were emptied into a hopper.

The mill had two pairs of rollers, the first one at the top and the at the bottom. At the top, we were supposed to take out any large stones or 'foreign objects before they entered the process, but quite often these got through and were ground up in the clay.

Next was the mincer, a set of rotating blades that churned and mixed up the clay.

Then came the second pair of rollers.

Finally at the bottom end, the smooth clay emerged, squeezed in a long tube about six inches thick - rather like toothpaste from a toothpaste tube. This was cut into manageable lengths of about 3 foot by a 'cheesewire', then stacked for use the following morning.

At the beginning of each day, the stacked clay was put through the bottom rollers one more time before being piled onto a battery-powered trolley for delivery to the potters around the works.

The power for the mill: the gas plant

contributed Frank Marden, pottery worker in the 1950s

The gas plant could produce its own gas by burning anthracite, or it could work off the main town gas supply.

It powered a six-foot diameter brass flywheel which generated electricity to drive the machinery around the works. All this was connected by belts.

The plant was operated by the boiler man, Harry Saywell, who seemed to spend all his time in there, even checking around at night with a torch. In fact, I’m sure he slept there sometimes! He would be constantly oiling and tinkering, and on occasions would search along the gas pipes for leaks with a naked flame!

Potters' wheels

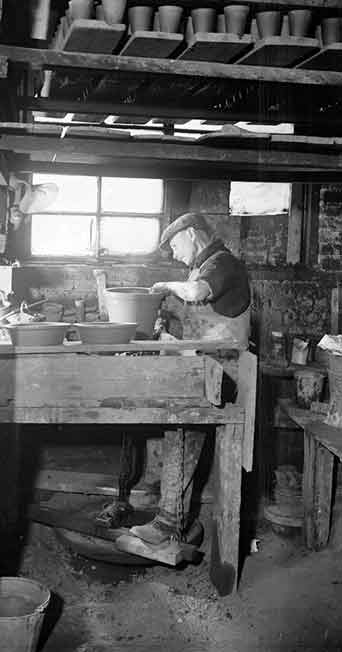

A potter's wheel is a device for creating a smooth, round object from a lump of clay. Today, with the arrival of plastic pots, the wheels are only used for by hobbyists, artisans and specialist potteries. At the Cole Pottery, however, before the arrival of plastics, the objects were flower pots of various sizes.

A potter's wheel consisted of a round, horizontal platform about 2 feet wide that was made to rotate.

The following description is best understood while referring to the following image.

In the early years of the Cole Pottery, the arrangement was exactly as shown in the image. The wheel was rotated by the backwards and forwards motion of the potter's foot on what was called a treadle attached to the wheel by a chain. This was just as I remember my mother's old sewing machine being powered by her feet on a treadle. Her treadle was metal and wide enough for both feet, but potters' ones were more like wooden pedals, as shown in the image.

The potter would start by picking up a lump of clay which had been suitably sized by trainee potters known as wedgers.

Then he would throw his lump of clay onto the centre of the wheel. If it was off-centre, the pot would be misshapen and ultimately collapse, unable to be recovered. It needed skill to hit the centre of the wheel precisely every time.

Once centred, the potter would use his hands to shape the clay while the wheel was rotating, and his foot to control the speed. The entire process was known as 'throwing' the pot.

It must have been extremely tiring for potters to treadle with a foot throughout the day, while shaping clay, day in and day out with their hands. Yet my mother seemed quite happy to treadle her sewing machine while manoeuvring fabric through the moving sewing needle. But doing two different things as once is never easy. Potters were certainly highly skilled.

In the 1950s, electric power was gradually replacing manual power for potters' wheels in the Cole Pottery.

from an interview with Sid Cole, owner of the Cole Pottery quoted in

TURNING OUT

250,000 FLOWER POTS EVERY WEEK

News of the Worldspecial

[dated from its

context as about 1935]

The older employees, who make the big flower pots still use the old-fashioned, foot-driven potter’s wheel, but the younger men use power-driven wheels which enable them to turn out as many as six pots a minute.

It takes six years to learn the potter's art, but a highly-skilled man can then turn out as many as 300 small flower-pots every hour.

In contrast, using foot-driven wheels, experienced potters could produce standard pots at the rate of two in just over a minute.

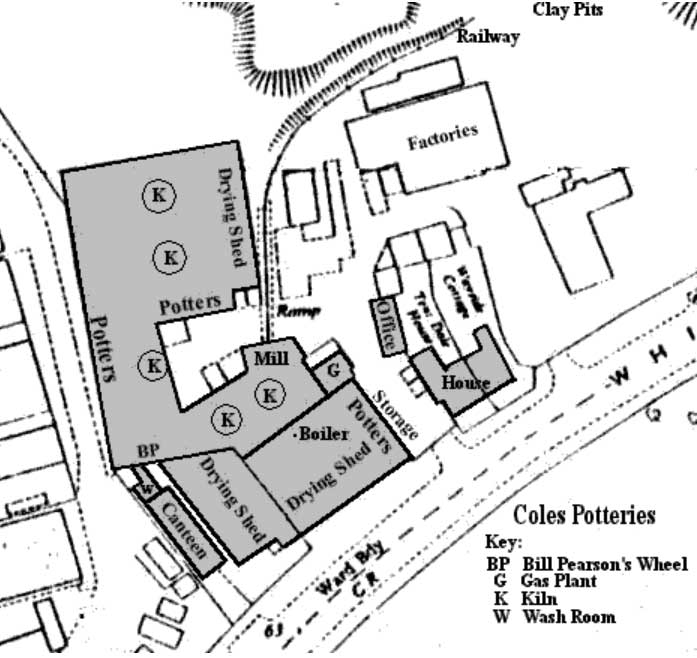

The potters' workshops

contributed Frank Marden, pottery worker in the 1950s

There were several workshops around the site, all containing lines of potters' wheels with foot activated pedals.

The potters produced various sizes of pot from the tiny two inch 'Tom Thumbs' (for plant cuttings etc.) to the biggest which were about twelve inches in diameter.

The large pots were the speciality of the senior potter Bill Pearson who had his personal wheel at the rear of the works near the canteen.

contributed David Marden, a child living at the pottery in the 1950s

The whole place was coated in a thick film of fine clay dust – including the canteen. The only internal evidence of electricity was a few light bulbs strung around at intervals under the roofing.

Marking maker's names on the pots

While still damp, the larger pots could be marked with the makers name.

The inscription tool was known as a roulette. It was placed against the pot and as the potter's wheel is rotated, it rotates too, leaving whatever impression is required, in this case the pottery name

Holding a roulette at Swallow Tiles. (Swallow Tiles closed in 2008.)

Clay plant pot marked round with a roulette, reading Tottenham Cole * Tottenham Cole * ...

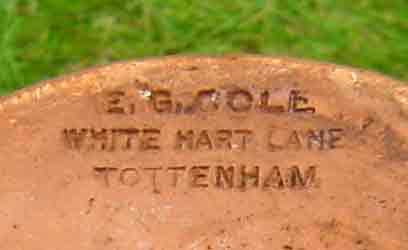

In the early days of the Cole pottery when it produced sample ware other than plant pots, some of the products had flat bases. Then the name of the pottery was stamped on the base.

Base of early Cole garden ornament showing makers name stamped on

The drying sheds

contributed Frank Marden, pottery worker in the 1950s

The finished pots had to be dried to prevent cracking during firing, a process that took several days.

The pots were placed on wooden boards which were stacked in the drying sheds heated by hot water pipes running round the walls. For ease of transport, these drying sheds were located behind the potters' workshops.

The drying process took several days.

The boilerman was a smallish chap who was always covered in grime. He once had a short spell in hospital and when he returned everyone stared at him for a while. Nobody recognised him because of his clean face!

Glaze or no glaze

Once pots were dry, they could be glazed. In the early days of the Cole Pottery, a few items were coloured and glazed to serve as ornaments, shiny and of course waterproof.

Coloured and glazed Cole jug made in the early 1900s before the pottery concentrated on flower pots

However, glazing was discontinued because the fumes killed neighbouring trees. A number of gaunt, dead trees were reported in the vicinity in the first couple of decades of the 1900s. One is clearly visible in the following sketch of the pottery house.

One of several dead trees caused by fumes from the pottery kilns before the pottery specialised only in plant pots

A feature of the unglazed flower pots compared with the glazed - and later the plastic ones - was said to be that they let the plant roots 'breathe. However, later experience with plastic pots shows that 'breathing' seems to be entirely unnecessary. The 'breathing' was probably a myth or marketing strategy.

Firing and the kilns

Once dry, the pots were ready for firing. There were five kilns and one or other of them was in use all the time.

David Marden's sketch from memory of the Cole Pottery in the 1950s showing five kilns

contributed Frank Marden, pottery worker in the 1950s

The pots were loaded into a kiln for firing, placed on shelves supported by fire bricks.

It was a precise job getting the various sizes at the right levels and with correct amount of spacing between them.

When the kiln was full, the doorway was bricked up and the fire grates around the outside were lit to produce the heat inside.

Kilns were fired for about a week at a temperature of 940 degrees centigrade, and progress could be monitored by removing one of the door bricks at eye level.

When the process was over, the kiln was allowed to cool for about three days before the contents could be emptied. Even so, emptying was very hot and exhausting work. A gang of five would take the best part of a morning to clear a kiln, taking turns to climb up to the shelves and throw down the pots to another worker. This worker stacked the pots into barrows and wheeled them outside for storage in the yard. Particular care had to be taken on cold mornings as a sudden change in temperature would crack the pots.

recollected by Florence Cole, later Florence Clarke, from her childhood at the Cole Pottery in the 1910s

The kilns were not unlike Eskimo igloos to look at.

I was puzzled at my mother's description of the kilns as like igloos. After all, doesn't everyone know that kilns were cone shaped with a chimney at the top?

[add images of common ideas of kilns]Yet my mother's recollections elsewhere on this website have proved completely accurate. So I probed further and it turned out that she was also right on this too:

I asked ChatGPT about the issue. Apparently, the 'centrally vented system' as it was called was fairly uncommon in the UK, although more common in Europe. It worked rather in the same way as the fireplaces-chimney arrangement in the different rooms of a house. Fires in the fireplaces can be lit independently while carrying their smoke and hot gases to one single chimney. Kilns using the system were similarly ducted to one single tall chimney. The ducts went round the kiln area, then underground to the single tall chimney, strategically placed somewhere.

As confirmation of this kiln system being in use at the Pottery, no tall bottle kilns appear in any of the paintings and photographs of the pottery site, whereas a single tall chimney can just be seen in the centre of the following sketch.

Tall narrow chimney from the 'centrally vented' kilns system

Also, David Marden mentions the width of the kilns in the following contribution with no mention of any particular height.

contributed David Marden, a child living at the pottery in the 1950s

I think the kilns were about ten feet wide with say, six or eight fire grates around the outside.

Delivery

contributed Frank Marden, pottery worker in the 1950s

The pots for delivery were placed all along the side of the yard, under cover in shelters which were just wooden roofs on supports. Also along the side of the yard were coal bunkers and storage areas for stacking finished pots.

In the early years of the pottery, local deliveries would have been by horse and cart. I do, though, have photos from as early as the beginning of the 20th century, showing deliveries of various other commodities by petrol-driven vehicles. So maybe the pots were vehicle delivered from quite early on.

contributed Frank Marden, pottery worker in the 1950s

Pots were often delivered as far afield as 100 miles.

recollected by Florence Cole, later Florence Clarke, from her childhood at the Cole Pottery in the 1910s

There was a large map of England on the office wall for the deliveries. Yes, the whole of England. I saw it when I was told to take a cup of coffee along to the office.

I wish I knew more about how the pots were delivered and where to. I know from the above snippet of information from my mother that the entire country was in management thinking, but how was this organised? If you know, please get in touch via the contact page.

| sources | webmaster | contact |

Text and images are copyright

If you can add anything to this page or provide a photo, please contact me.